📚 The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel

🎯 Read This Book If

You want to explore the strange ways people think about money and learn how to make better sense of one of life’s most important topics: money.

🔑 Key Points

- Investing is more of a soft skill than a hard science, where our own experience and behaviour can be more important than the technical side of money.

- We don't give enough weight to the things that really matter, this can lead us to risk what we have and need, for what we don't have and don't need.

- Our long term success as investors comes down to our ability to: identify what matters most, and build a plan that we can stick to towards those goals.

🤔 Detailed Summary

The Greatest Show On Earth

Money impacts all of us, regardless of what direction our lives take us. Doing well with money has little to do with how smart you are and a lot to do with your behaviour. Which is hard to teach, even to really smart people.

A genius who loses control of their emotions can be a financial disaster. The opposite is true. Ordinary folks with no financial education can be wealthy if they have a handful of behavioural skills that have nothing to do with formal measures of intelligence.

Ronald Read was a high school graduate who worked as a gas station attendant and janitor. His life was as low key as they come, a friend said Read’s favourite hobby was chopping wood. Read was completely unknown until his death in 2014, at age 92. Remarkably, he died with a net worth of $8 million. A surprise to everyone that knew him. He left $2 million to his step-kids, and more than $6 million to a local hospital and library. Read had no secret to his success. Over his life, he invested in blue chip stocks, and waited. That was all that was needed to take Read from janitor to philanthropist.

A few months before Read was in the news, Richard Fuscone was there. Fuscone was a Harvard-educated Merrill Lynch executive, who retired in his 40’s to become a philanthropist. He was everything that Read was not. But Fuscone borrowed heavily to expand his 18,000 square foot Connecticut house. Then the 2008 financial crisis hit. His high debt and illiquid assets left him bankrupt, at one point stating ‘I currently have no income’.

Ronald Read was patient; Richard Fuscone was greedy. That’s all it took to eclipse the massive education and experience gap between the two.

What’s fascinating is how unique this is to finance. There's no other profession where an uneducated and untrained person, can find the outcome that alludes someone with the best education and experience. Why is it possible for this to happen in finance? Maybe our financial success just comes down to luck. More likely, investing is more of a soft skill (emotions and nuance) than a hard science (rules and laws), where our behaviour is more important than the technical side of money.

It’s that knowing what to do tells you nothing about what happens in your head when you try to do it.

We can find definitive answers with most problems in life. An engineer can determine the cause of a bridge collapse, because physics isn't controversial, it's guided by laws. Finance on the other hand is completely different, it's guided by people's behaviours.

History never repeats itself; man always does.

No One’s Crazy

Your personal experiences with money make up maybe 0.00000001% of what’s happened in the world, but maybe 80% of how you think the world works.

Everyone has their own unique experience with how the world works. So all of us go through life anchored to a different set of views on how money really works. What seems crazy to you, might make complete sense to me.

Studying history makes you feel like you understand something. But until you've lived through it and felt its consequences, you may not understand it enough for it to change your behaviour. As investor Michael Batnick said, "some lessons have to be experienced for they can be understood."

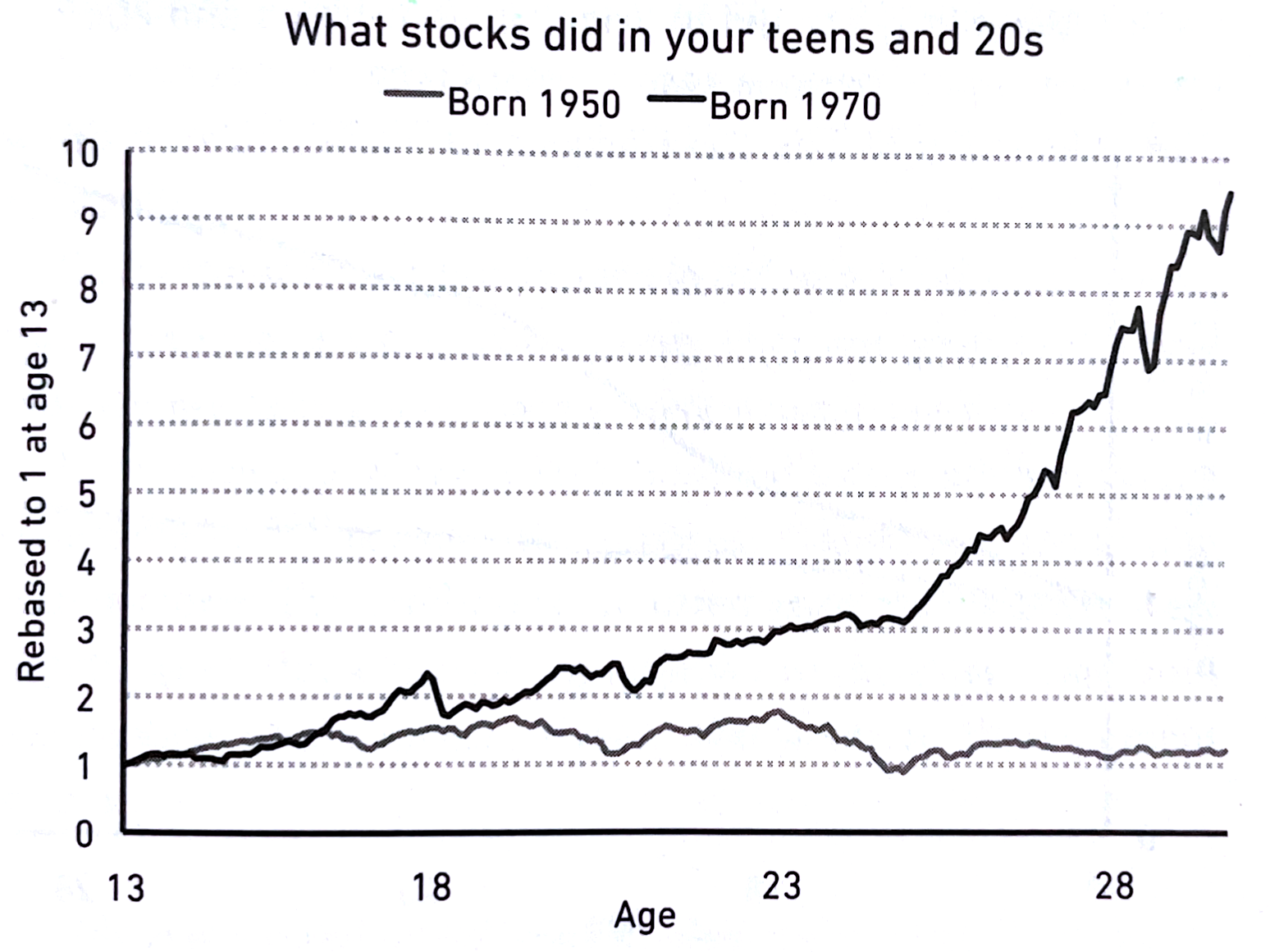

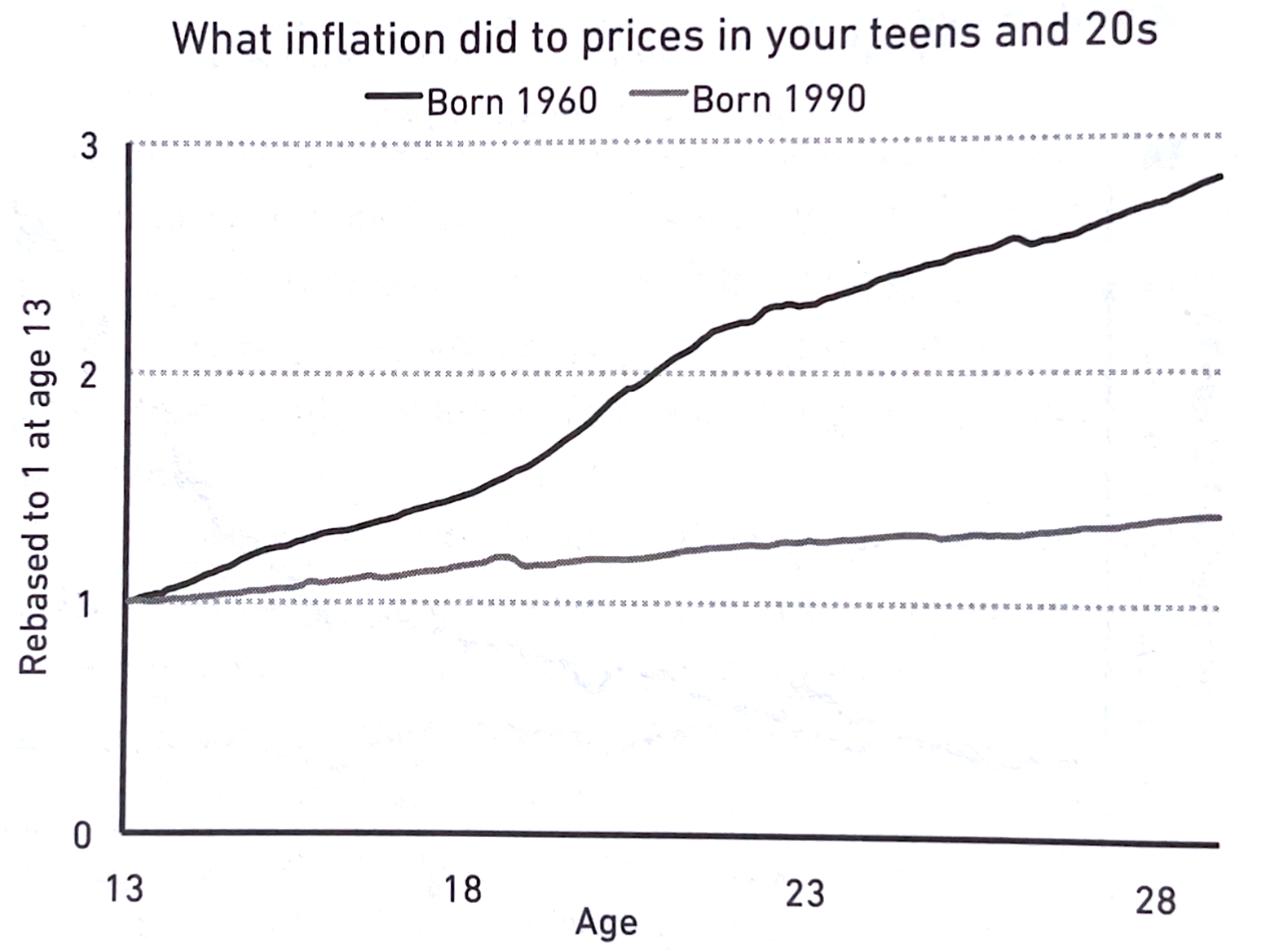

People's lifetime investment decisions are heavily anchored to the experience they had in their own generation, especially early in their life. Research suggests that individual investors' willingness to bear risk depends on their personal history. Depending on when two people were born, they could have completely different views on how the stock market works.

Or what kind of impact inflation has on our finances.

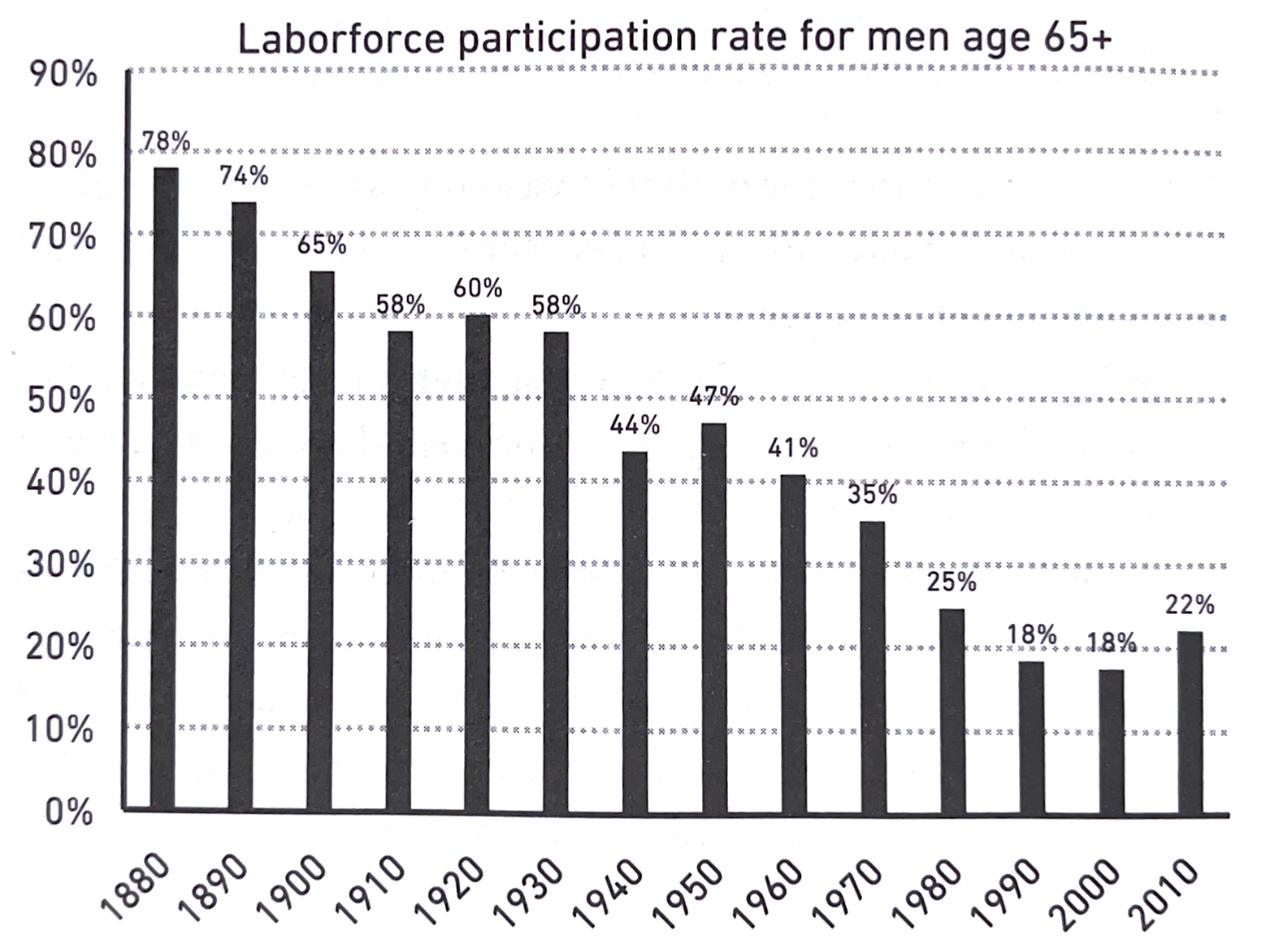

A universally accepted concept, retiring, is only a few generations old. Prior to WWII, most American's worked until they died. It wasn't until after the war that we started to see the majority of the male workforce age 65 and older begin to stop working.

Most of what we know of our current financial system: account types, investment options, funds, mortgages, credit cards, loans, are all only a matter of being decades old.

We all do crazy stuff with money, because we're all relatively new to this game and what looks crazy to you might make sense to me. But no one is crazy – we all make decisions based on your own unique experiences that seem to make sense to us in a given moment.

Luck & Risk

Nothing is as good or as bad as it seems.

In 1968, Lakeside School teacher Bill Dougall petitioned that available funds should be used to lease a Teletype Model 30. In 1968, that's where Bill Gates, Paul Allen, and Kent Evans attended school. Three very bright students that quickly became obsessed with the computer. Only seven years later, Gates and Allen would go on to cofound Microsoft. Evans, unfortunately was killed in a mountaineering accident prior to graduation.

In 1968, there were roughly 303 million high school age people in the world, 18 million in the US, 270,000 in Washington State, 100,000 in the Seattle area, and only 300 attended Lakeside School. Gates and Allen each experienced one in a million odds of attending Lakeside School. Evans on the other hand experienced one in a million odds of being killed in high school on a mountain. They all faced the same odds, just in different directions.

"If there had been no Lakeside, there would have been no Microsoft.", Bill Gates

Luck and risk both play significant roles in success. Luck can inflate our success, and risk can deflate our success. A fundamentally bad decision can turn out good with a little luck, while a fundamentally good decision doesn't always go our way. It's important to recognize the role of luck and risk, and how it impacts our outcomes. There's two things we can look towards that can point us in a better direction:

- Be careful who you praise and admire. Be careful who you look down upon and wish to avoid becoming.

- Therefore, focus less on specific individuals and case studies and more on broad patterns.

"Success is a lousy teacher. It seduces smart people into thinking they can't lose.", Bill Gates

Never Enough

When rich people do crazy things.

Rajat Gupta, Raj Rajaratnam, and Bernie Madoff are just a few people who had incredible success, but had no sense of enough. A drive to try to get even more, drove them to criminal activity, in some cases losing everything and then some.

There is no reason to risk what you have and need for what you don't have and don't need.

Few of us will ever have the money they had, but we all strive to have enough money to cover every reasonable thing we need, or a lot of what we want. When you get there, remember:

- The hardest financial skill is getting the goalpost to stop moving – modern capitalism is a pro at two things: generating wealth and envy.

- Social comparison is the problem here – the ceiling of social comparison is so high that virtually no one will ever hit it.

- "Enough" is not too little – "Enough" is realizing that an insatiable appetite for more will push you to the point of regret.

- There are many things never worth risking, no matter the potential gain – your best shot at keeping things is knowing when it's time to stop taking risk that might harm them.

Happiness, as it's said, is just results minus expectations.

Confounding Compounding

$81.5 billion of Warren Buffett’s $84.5 billion net worth came after his 65th birthday. Our minds are not built to handle such absurdities.

If Warren Buffet only invested from age 30 until retirement at 60 (assuming his annual return of 22%), his net worth would be 99.9% less than what it is today. His skill is investing, but his secret is time.

If I ask you to calculate 8+8+8+8+8+8+8+8+8 in your head, you can do it in a few seconds (it's 72). If I ask you to calculate 8x8x8x8x8x8x8x8x8, your head will explode (it's 134,217,728). The danger is that when compounding isn't intuitive, we ignore its potential and focus on solving problems through other means. We often look at earning the highest investment returns as a way to get success, it intuitively seems like the best way to get rich.

But good investing isn't necessarily about earning the highest returns, because the highest returns tend to be one-off hits that can't be repeated. It's about earning pretty good returns that you can stick with and which can be repeated for the longest period of time. That's when compounding runs wild.

Getting Wealthy vs Staying Wealthy

Good investing is not necessarily about making good decisions. It’s about consistently not screwing up.

There are a million ways to get wealthy, but only one way to stay wealthy: a combination of frugality and paranoia. If I had to summarize money success in a single word, it would be survival.

Getting money requires taking risks, being optimistic, and putting yourself out there. But keeping money requires the opposite of taking risk. It requires humility, and fear that what you've made can be taken away from you just as fast.

Compounding only works if you give an asset decades to grow. Getting and keeping that growth requires surviving all of the unpredictable ups and downs that we all experience. We can point to what Buffett did to make himself successful, but we can also point to what he didn't do: carry high debt, panic sell during the 14 recessions he's lived through, ruin his reputation, believe he was always right, rely on others money, burn himself out or quit. He survived.

The survival mindset in the real world comes down to appreciating three things:

- More than I want big returns, I want to be financially unbreakable. And if I'm unbreakable I actually think I'll get the biggest returns, because I'll be able to stick around long enough for compounding to work wonders.

- Planning is important, but the most important part of every plan is to plan on the plan not going according to plan.

- A barbelled personality – optimistic about the future, but paranoid about what will prevent you from getting to the future – is vital.

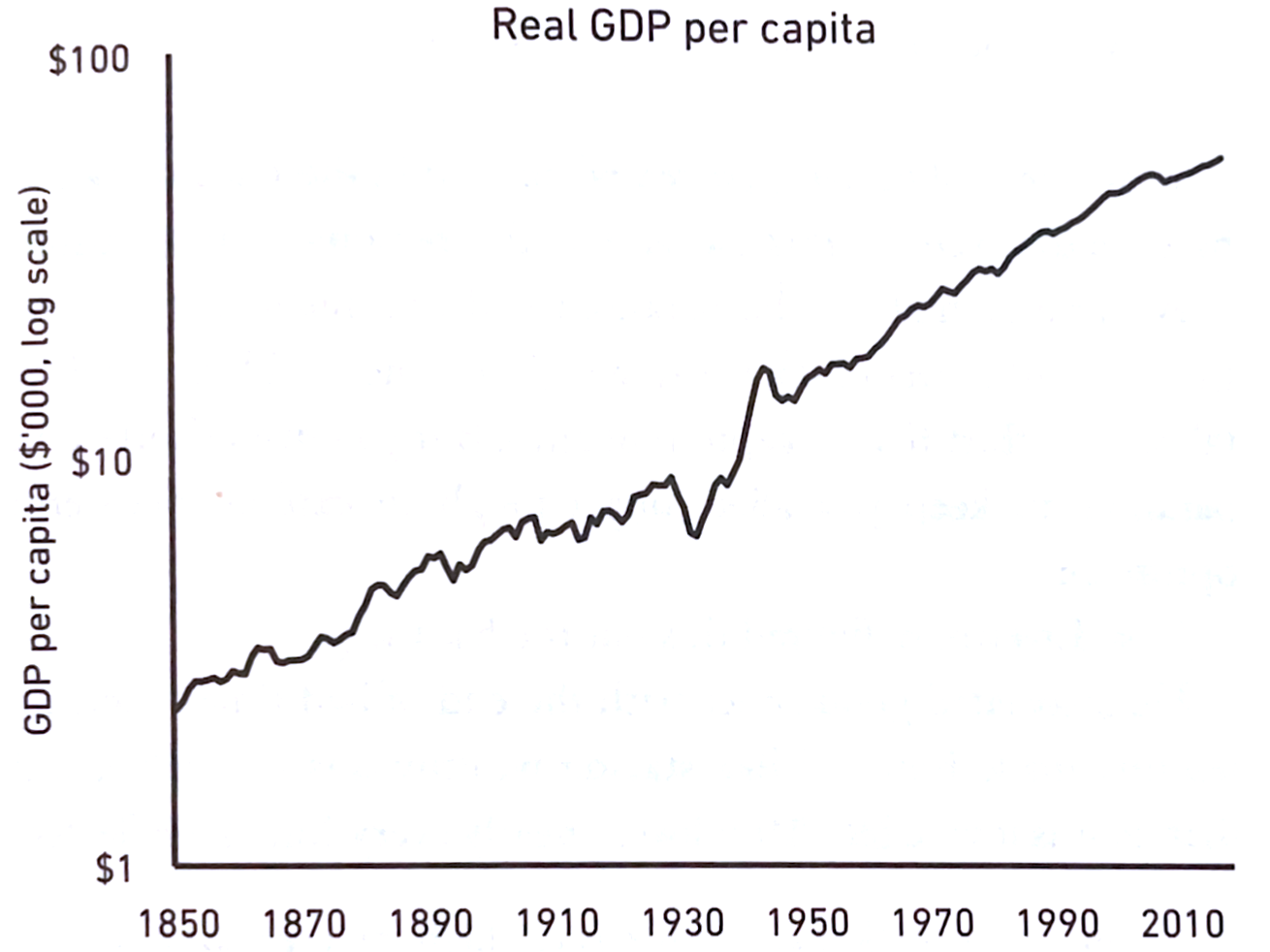

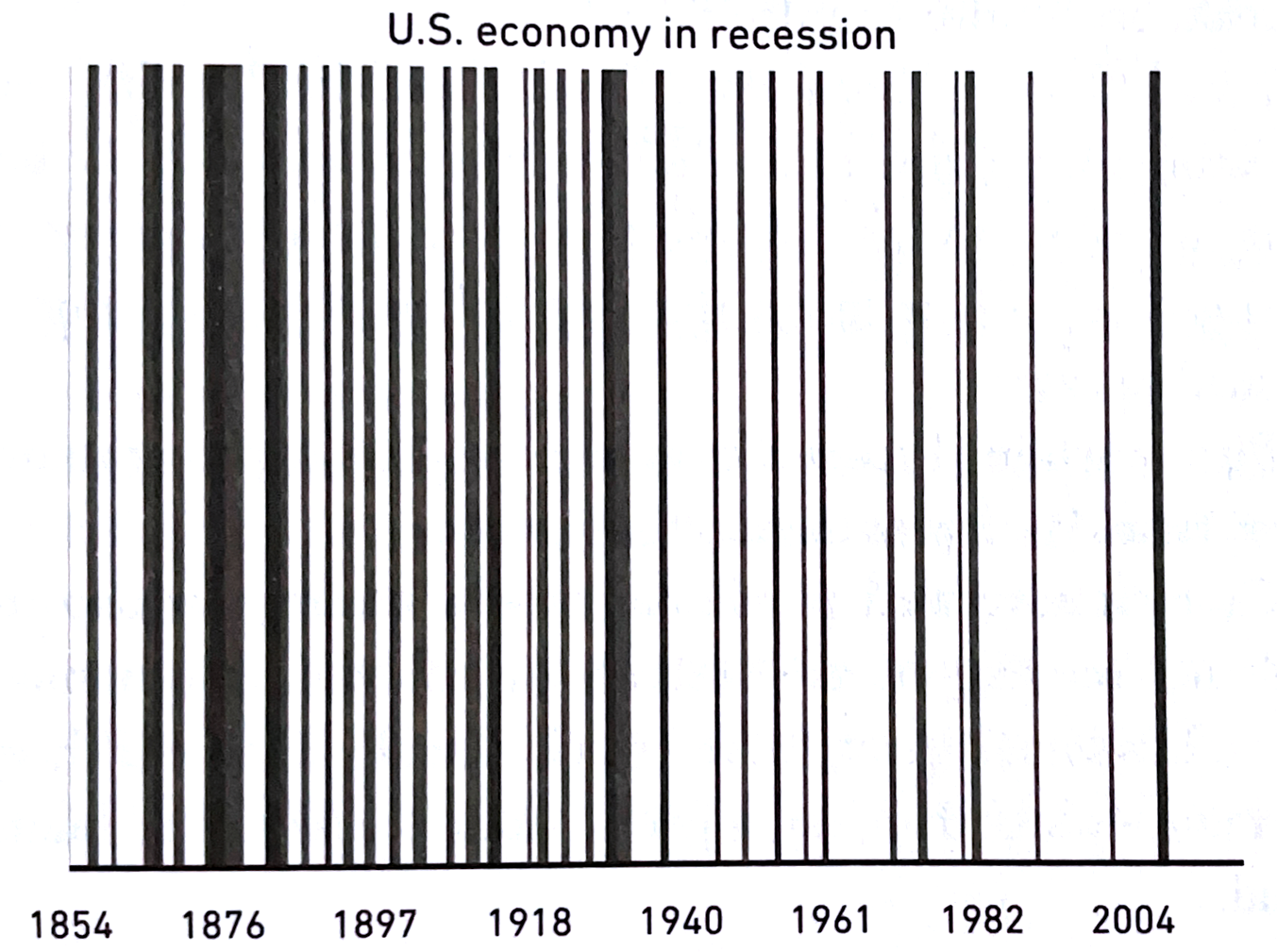

Here's how the US economy performed over the last 170 years:

All during a time where:

- 1.3 million Americans died in 9 major wars.

- Roughly 99.9% of companies created went out of business.

- Four US presidents were assassinated.

- 675,000 died in a single year from a flu pandemic.

- 30 different natural disasters each killed at least 400 Americans.

- 33 recessions lasted a cumulative 48 years.

- The number of forecasters who predicted any of those recession rounds to zero.

- The stock market fell more than 10% from a recent high at least 102 times.

- Stocks lost 1/3 of their value at least 12 times.

- Annual inflation exceeded 7% in 20 separate years.

- "Economic Pessimism" appeared in newspapers at least 29,000 times.

Our standard of living increased 20-fold in the 170 years, but barely a day went by that lacked tangible reasons for pessimism.

Tails, You Win

You can be wrong half the time and still make a fortune.

By the mid-1930s, Disney had produced more than 400 cartoons, most of them were short, loved, and lost a fortune. But everything changed with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, earning enough to make Disney an incredible success. Disney was wrong hundreds of times, but right once in a very big way, and that's all that mattered.

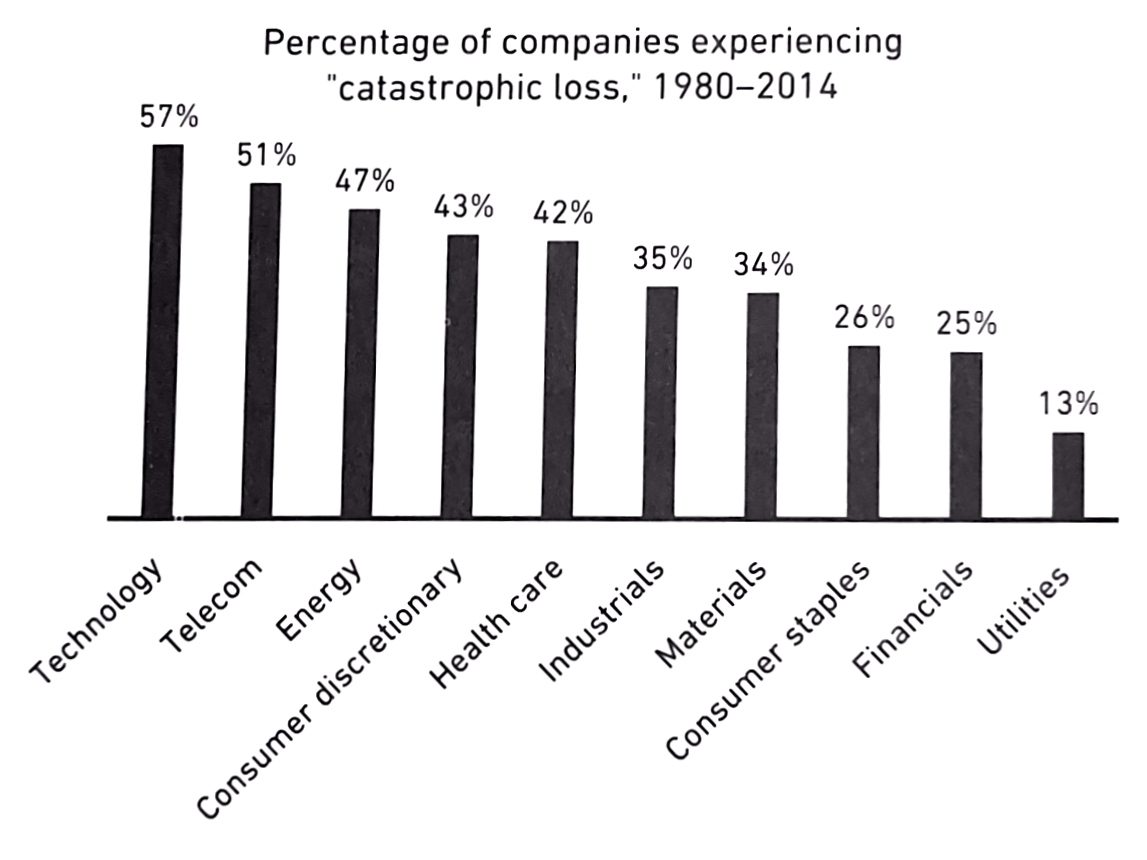

Most public companies are duds, a few do well, and a handful become extraordinary winners that account for the majority of the stock market's returns.

Investor success is determined by how you respond to punctuated moments of terror, not the years spent on cruise control. A good definition of an investing genius is the person who can do the average things when all those around them are going crazy.

There are professions where you must to be perfect every time, like a pilot. And professions where you need to be at least pretty good nearly all the time, like a chef. Finance, business, investing, they aren't like that. You can be wrong or average a lot, and end up with incredible results.

"It's not whether you're right or wrong that's important, but how much money you make when you're right and how much you lose when you're wrong.", George Saros

Freedom

Controlling your time is the highest dividend money pays.

The highest form of wealth is the ability to wake up every morning and say, "I can do whatever I want today." Happiness is complicated because it looks different for everyone, but there's a common source of joy: everyone wants to control their lives. Control over what you do, is the broadest lifestyle variable that makes people happy.

Having a strong sense of controlling one's life is a more dependable predictor of positive feelings of wellbeing than any of the objective conditions of life we have considered.

Using your money to buy time and options has a lifestyle benefit few luxury goods can compete with. Doing something you love on a schedule you can't control can feel the same as doing something you hate. The problem is as we've become wealthier, we've used our wealth to buy more stuff, wiping out the progress that should have been made.

Compared to generations prior, control over your time has diminished. And since controlling your time is such a key happiness influencer, we shouldn't be surprised that people don't feel much happier even though we are, on average, richer than ever.

Man in the Car Paradox

No one is impressed with your possessions as much as you are.

We buy expensive things thinking it will make people admire us. Think back to the last time you saw a nice car, like really really nice car. Did you think about the driver for even a split second? Of course not, you were too busy admiring the car.

People tend to use wealth to signal to others how wealthy they are, thinking that it'll make them liked and admired. The reality is those people who we want to admire us, don't, and instead use our wealth as a benchmark for their own desire to to be admired. It almost never works as a way to gain admiration, especially from those who we hope will give it to us.

If respect and admiration are your goal, be careful how you seek it. Humility, kindness, and empathy will bring you more respect than horsepower ever will.

Wealth is What You Don’t See

Spending money to show people how much money you have is the fastest way to have less money.

We tend to judge wealth on what we see. But money has a lot of ironies, maybe the biggest is: wealth is what you don't see. When you see someone driving a $100,000 car, the only data point you have is that they have $100,000 less than they did before buying that car.

Wealth is about accumulating assets, and only spending money that you already have, not money you don't have. Rich is current income, wealth is hidden, it's income not spent. The default that's been ingrained in us is to have money is to spend money, that thinking takes away the opportunity to build wealth.

The world is filled with people who look modest but are actually wealthy and people who look rich who live at the razor's edge of insolvency.

Save Money

The only factor you can control generates one of the only things that matter. How wonderful.

Above a certain level of income, there are three groups of people: those who save, those who think they can't save, and those who think they don't need to save. Here are some tips for those last two groups:

- The first idea – simple, but easy to overlook – is that building wealth has little to do with your income or investment returns, and lots to do with your savings rate.

Since you can build wealth without a high income, but have no chance of building wealth without a high savings rate, it's clear which one matters more.

- More importantly, the value of wealth is relative to what you need. Past a certain level of income, what you need is just what sits below your ego.

People with enduring personal finance success tend to have a propensity to not give a damn what others think about them.

- So people's ability to save is more in their control than they might think.

Money relies more on psychology than finance.

- And you don't need a specific reason to save.

Saving is a hedge against life's inevitable ability to surprise the hell out of you at the worst possible moment.

- That flexibility and control over your time is an unseen return on wealth. And that hidden return is becoming more important.

Having more control over your time and options is becoming one of the most valuable currencies in the world. That's why more people can, and more people should, save money.

Reasonable > Rational

Aiming to be mostly reasonable works better than trying to be coldly rational.

When making financial decisions, instead of being coldly rational, aim to be pretty reasonable. It's more realistic and gives you a better chance at sticking to it over the long-term. Which, is what matters most when it comes to managing our money. We make decisions everyday that might be irrational, but are completely reasonable to us and what we're trying to do.

We can understand the math behind why investing works, but what's more important, is to feel an emotional connection to our investments. Emotion keeps us committed, and the longer we invest for, the greater our chance of success. Whether it's believing in the outcome our investments will bring us, the companies we invest in, or the strategy itself, we could benefit by falling in love, just a little bit, with our investments.

"I visualized my grief if the stock market went way up and I wasn't in it – or if it went way down and I was completely in it. My intention was to minimize my future regret.", Harry Markowitz

Surprise!

History is the study of change, ironically used as a map of the future.

We can look to the past to see what has happened, but the only thing we can know moving forward is that things might be: the same, worse, or better. Science can't capture emotion into equations. So even two situations that look identical on paper, could have drastically different outcomes.

"Things that have never happened before happen all the time.", Scott Sagan

When we rely too heavily on history, a couple of things can happen:

- You'll likely miss the outlier events that move the needle the most.

The majority of what's happening at any given moment in the global economy can be tied back to a handful of past events that were nearly impossible to predict.

- History can be a misleading guide to the future of the economy and stock market because it doesn't account for structural changes that are relevant to today's world.

The S&P 500 did not include financial stocks until 1976; today, financials make up 16% of the index. Technology stocks were virtually nonexistent 50 years ago. Today, they're more than a fifth of the index.

The financial landscape is constantly evolving, just like it always has. With each decade we look back at, we see more and more that was once essential, that no longer applies to today. The further back we look, the less specific and more general our takeaways should be.

Room for Error

The most important part of every plan is planning on your plan not going according to plan.

We don't know what will happen in the future, but we can do things that shift the odds in our favour. Probability doesn't mean certainty. Using a margin of safety; cash on hand or conservative returns; might sound conservative but it's the opposite. Having cash provides a buffer so our investments can continue to work, using conservative returns makes us more aggressive with our savings rate.

Since the future is unknown, what will go wrong is also a mystery. We need to do things that allow us to play the game of investing for as long as possible. Because the longer we play the better our results become.

The biggest single point of failure with money is a sole reliance on a pay check to fund short-term spending needs, with no savings to create a gap between what you think your expenses are and what they might be in the future.

You’ll Change

Long-term planning is harder than it seems because people's goals and desires change over time.

People are poor forecasters of their future selves. Just compare what you do for a living now, to the very first thing you wanted to be when you grew up. Only 27% of college grads have a job related to their major. 29% of stay at home parents have a college degree. It's tough to make enduring long-term decisions, when your view of what you'll want in the future is so likely to shift. Two things to remember:

- We should avoid the extreme ends of financial planning.

Aiming, at every point in your working life, to have moderate annual savings, moderate free time, no more than a moderate commute, and at least moderate time with your family, increases the odds of being able to stick with a plan and avoid regret than if any one of those things fall to the extreme sides of the spectrum.

- We should also come to accept the reality of changing our minds.

Sunk costs – anchoring decisions to past efforts that can't be refunded – are a devil in a world where people change over time. They make our future selves prisoners to our past, different, selves. It's the equivalent of a stranger making major life decisions for you.

Nothing’s Free

Everything has a price, but not all prices appear on labels.

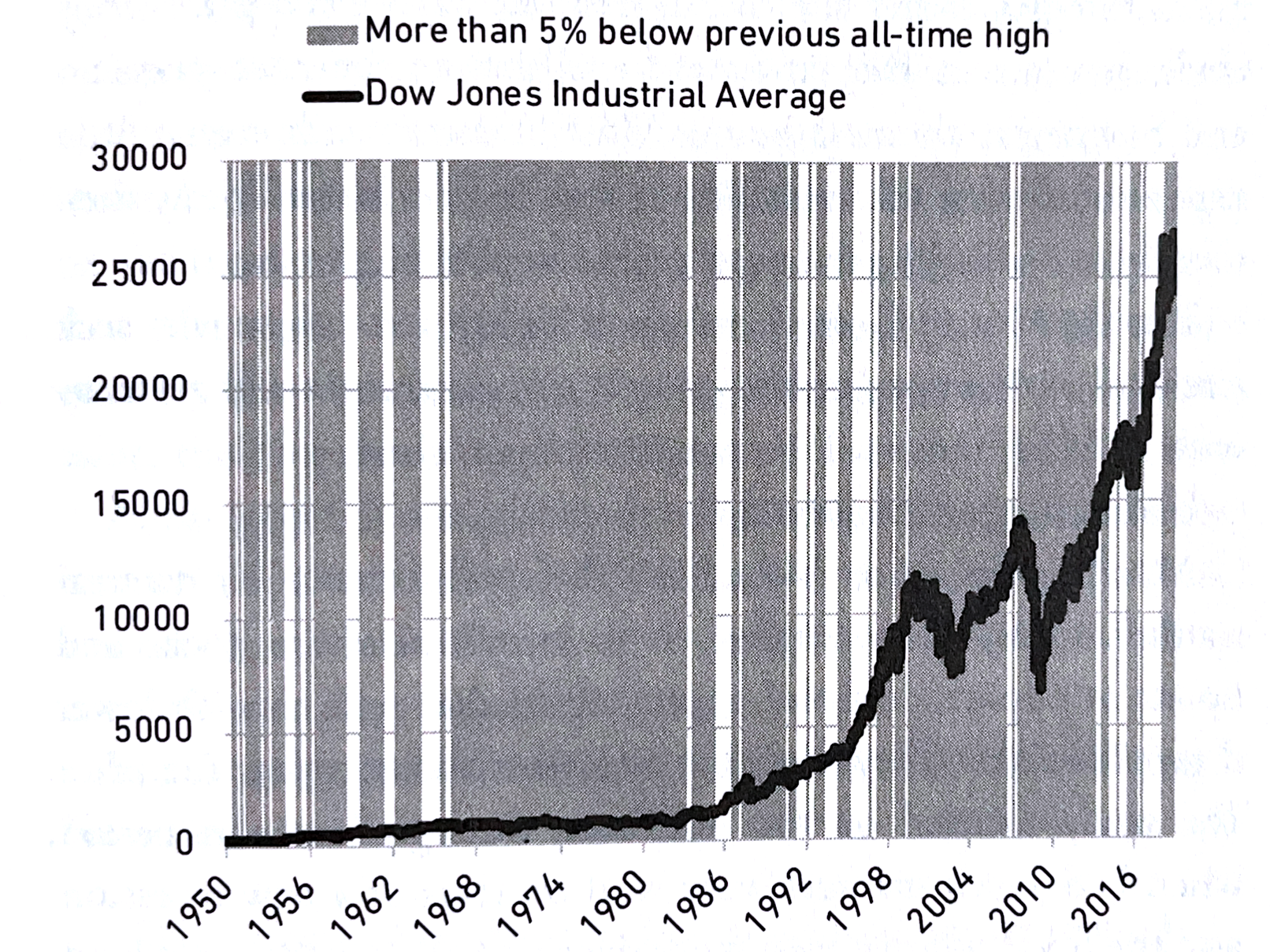

The price we pay as investors isn't in the form of dollars. It's in the form of volatility, fear, doubt, uncertainty and regret. In the chart below, the DJIA averaged an annual return of 11%. Even with the phenomenal return, you can see that the majority of the time the index was more than 5% below a previous all-time high. Investors earned those returns.

Like most products, the bigger the returns, the higher the price. Netflix stock returned more than 35,000% from 2002 to 2018, but traded below its previous high on 94% of days.

Investors may try to boost returns by jumping to hot stocks in order to avoid downtrends, but we often meet our destiny by trying to avoid it. By trying to avoid downtrends for the sake of gains, investors actually underperform compared to if they had stayed the course.

For many things we're fine with paying a fee once we convince ourself that it's worth it. Like going to Disney World, the high fee for admission is more than worth the fun you'll have. We just have to do the same with investing. Markets always charge and receive their fee. You can pay your fee in volatility, or you can pay your fee in cash, the choice is yours.

You & Me

Beware taking financial cues from people playing a different game than you.

With the amount of bubbles, recessions, and financial mistakes from the past, it might make you wonder why they still happen, why we haven't learned our lesson. It's impossible to diagnose at the time, only in hindsight do the signals become clear, even if the cause isn't agreed on.

But let me propose one reason they happen that both goes overlooked and applies to you personally: Investors often innocently take cues from other investors who are playing a different game than they are.

We all invest for our own reasons, and on our own timeline. Even if we share a similar goal, it won't look identical as someone else's. Bubbles form when short-term momentum attracts enough money to shift investors from mostly long-term to mostly short-term. We invest for a lot of different reasons, and it's dangerous to assume someone's reasons are the same as yours. The key is to know what game you're playing, and continue to play it.

A takeaway here is that few things matter more with money than understanding your own time horizon and not being persuaded by the actions and behaviours of people playing different games than you are.

The Seduction of Pessimism

Optimism sounds like a sales pitch. Pessimism sounds like someone trying to help you.

Optimism isn't the belief that everything is always great, it's the belief that, despite setbacks, the odds of a good outcome are in your favour. Optimism is usually met with a shrug and eye roll, while pessimism holds onto the undivided attention it grabs. It might be evolutionary, treating threats with urgency leads to better odds of survival. Here's some reasons why pessimism dominates headlines:

- One is that money is ubiquitous, so something bad happening tends to affect everyone and captures everyone's attention.

There are two topics that will affect your life whether you are interested in them or not: money and health. While health issues tend to be individual, money issues are more systematic. In a connected system where one person's decisions can affect everyone else, it's understandable why financial risks gain a spotlight and capture attention in a way few other topics can.

- Another is that pessimists often extrapolate present trends without accounting for how markets adapt.

Assuming that something ugly will stay ugly is an easy forecast to make. And it's persuasive, because it doesn't require imagining the world changing. But problems correct and people adapt. Threats incentivize solutions in equal magnitude.

- A third is that progress happens too slowly to notice, but setbacks happen too quickly to ignore.

Growth is driven by compounding, which always takes time. Destruction is driven by single points of failure, which can happen in seconds, and loss of confidence, which can happen in an instant.

When You’ll Believe Anything

Appealing fictions, and why stories are more powerful than statistics.

Between 2007 and 2009, only one thing changed: the stories we told ourselves about the economy. In 2007, the story was about the stability of housing, the prudence of bankers, and the ability of markets to accurately price risk. In 2009, we stopped believing that story, and inflicted narrative damage on ourselves.

Stories are the most powerful force in the economy, stories can step on the gas or slam on the brakes. There's two things to remember when managing your money:

- The more you want something to be true, the more likely you are to believe a story that overestimates the odds of it being true.

The bigger the gap between what you want to be true and what you need to be true to have an acceptable outcome, the more you are protecting yourself from falling victim to an appealing financial fiction.

- Everyone has an incomplete view of the world. But we form a complete narrative to fill in the gaps.

Coming to terms with how much you don't know means coming to terms with how much of what happens in the world is out of your control. And that can be hard to accept.

All Together Now

What we’ve learned about the psychology of your own money.

Since we all have unique situations, it's important to make decisions and get advice, that's based on you. Here are some short recommendations that can help you make better decisions with your money:

- Go out of your way to find humility when things are going right and forgiveness/compassion when they go wrong.

- Less ego, more wealth.

- Manage your money in a way that helps you sleep at night.

- If you want to do better as an investor, the single most powerful thing you can do is increase your time horizon.

- Become OK with a lot of things going wrong. You can be wrong half the time and still make a fortune.

- Use money to gain control over your time.

- Be nicer and less flashy.

- Save. Just save. You don't need a specific reason to save.

- Define the cost of success and be ready to pay it.

- Worship room for error.

- Avoid the extreme ends of financial decisions.

- You should like risk because it pays off over time.

- Define the game you're playing.

- Respect the mess.

There are universal truths in money, even if people come to different conclusions about how they want to apply those truths to their own finances.

Confessions

The psychology of my own money.

We play our own game. There are a lot of lessons in this book, but some will be more relevant to you than others. You could take all of the advice, none of it, or somewhere in between. It's really up to you. The important thing is to make decisions that make sense to you. Here's what works for Housel:

- How my family thinks about savings

I mostly just want to wake up every day knowing my family and I can do whatever we want to do on our own terms.

- How my family thinks about investing

I can afford to not be the greatest investor in the world, but I can't afford to be a bad one.

By identifying what matters most, and building a flexible plan to work towards it, you can focus on what makes sense to you. What you want will shift over time, but the main direction will look the same, and will rely on the same key behaviours: a high savings rate, patience, and optimism about the future. Remember, no one is crazy.

🧠 Final Thoughts

If I could only recommend one book moving forward, this would be it. Housel's ability to combine captivating storytelling and powerful lessons on money, creates a book that anyone can read, learn from, and enjoy – regardless of your education, or interest in finance.

The more I learn about investing, the more I realize how much there is to know. It's easy to think of investing as just numbers, that you can calculate your way to success. But it's obvious that it's much more than that. If there was a science to investing, we'd all do the exact same thing. But there are countless ways to invest, and although there are some ways that are better or worse than others, most sit in a grey area where personal preference should be the deciding factor.

In most aspects of our lives we feel a pressure to be, what we perceive to be, a better version of ourselves. We should be richer, have nicer things, do more of what we see in other peoples highlight reels. Things we don't really want or need, and that actually take us further away from what matters most to us. That's driven purely by the way we think.

I like to say that, there's a lot of value in letting great thinkers influence how we think. It can open our minds to perspectives we couldn't see, considerations we hadn't thought of, and opinions we couldn't feel. It can make us better rounded, and give us a stronger foundation for our own beliefs. It can help us make better decisions for what really matters. Morgan Housel is a great thinker.

This book, and the lessons it contains are timeless. They were just as relevant 100 years ago as they are today, and as they will be 100 years from now. If you're only going to read one finance book in your life, this should be it.

❤️ Liked This? Check These Out

Same As Ever by Morgan Housel, a guide to what never changes

A Random Walk Down Wall Street by Burton G. Malkiel, the time-tested strategy for successful investing

Making Money Simple by Peter Lazaroff, the complete guide to getting your financial house in order and keeping it that way forever

All ideas, quotes, and illustrations are borrowed or based on The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel. To learn more, visit www.morganhousel.com.

Member discussion